They say there’s nothing new under the sun, and when it comes to stories that hold our attention it seems like the works of yesterday keep finding new life on the big screen. As an avid moviegoer and occasional bookworm, I’m always fascinated to learn about popular films I enjoy that were adapted from novels. Page to screen translations can be a mixed bag – sometimes the movie captures the spirit and drama of the book beautifully, other times key elements get lost in translation.

I decided to put together a list of 8 movies that were surprises to me to discover originated from books. Growing up, I watched some of these films without any knowledge of their literary roots. With any adaptation, reading the source material is the best way to compare, but I hope sharing this list will encourage some of you to check out these page-turners and feed your curiosity. Who knows, you may just find a new favorite book!

Apocalypse Now (1979)

While Apocalypse Now is set during the Vietnam War, it takes its basic plot and much of its spirit from Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness, written in 1899 about nineteenth-century colonialism in Africa.

Heart of Darkness tells the story of Marlow, a merchant marine captain who travels deep into the Congo River basin to search for an ivory trader named Kurtz. As Marlow journeys further into the African interior, he encounters increasing darkness and savagery, both in the locales and behaviors of colonial traders, slave laborers, and local Africans who are suffering horrific exploitation under the capitalist pursuits of Western colonialism. Kurtz himself has completely succumbed to the madness within and declared himself a god to the local natives.

Apocalypse Now translates this narrative to the violent context of the Vietnam War. Martin Sheen takes on the Marlow role as Captain Benjamin Willard, sent on a mission down the Nung River into remote areas of Cambodia to “terminate Colonel Kurtz’s command.” As in Heart of Darkness, Willard encounters escalating madness and chaos the further he travels, with Kurtz (played by Marlon Brando) having snapped and begun godlike worship by a Vietnamese tribe. While the settings and historical backdrop differ, Apocalypse Now maintains Conrad’s powerful critique of the savage deeds men will commit in the distant outposts of imperialism when cut off from society in a wilderness of their own moral making.

The Curious Case Of Benjamin Button (2008)

The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, the 2008 film directed by David Fincher, was adapted from a 1922 short story of the same name by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald’s story, published in Collier’s magazine, tells the fantastical and moving tale of a man who ages in reverse. Benjamin Button is born an old man and gradually becomes younger as the years pass. The story is told through the eyes of a wartime acquaintance of Button’s daughter as she recounts Benjamin’s strange life and their connection.

The film, starring Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett, remains quite faithful to Fitzgerald’s unconventional premise while expanding the narrative scope. It follows Button from birth in his 80-year-old body to death as a baby-like elderly man. Along the way, he forges friendships, finds love, and experiences both the joys and pains of a life lived backwards as the world around him marches steady into the future.

Both the short story and movie are ultimately meditations on the nature of time and how we attach meaning to different life stages. Benjamin Button’s anti-aging journey challenges standard perceptions of youth and old age. In Fitzgerald’s conception and Fincher’s cinematic interpretation, age is shown to be a human construct, and the essence of one’s humanity lies beyond any physical vessel. The film captures the bittersweet beauty and existential mystery at the core of Fitzgerald’s original tale.

Clueless (1995)

Jane Austen’s 1815 novel Emma follows the titular character, a wealthy, pretty, and clever young woman who resides with her widowed father in the fictional village of Highbury. Emma enjoys meddling in the romantic lives of her friends and family but harbors a selfish ignorance about love herself.

The 1995 teen comedy Clueless takes Emma’s storyline and characters and transplant them to Beverly Hills in the 1990s. Alicia Silverstone stars as Cher Horowitz, an attractive and wealthy high school student who loves fashion and playing matchmaker. Like Emma, Cher has good intentions but can be misguided in her antics.

Both works focus on a lively heroine who considers herself quite adept at understanding others when in fact she lacks self-awareness. Emma and Cher each attempt to pair various friends together through manipulation and misconceptions, leading to comic chaos and lessons in humility. While the setting and dialogue are updated for a modern teenage audience, Clueless faithfully follows Austen’s plot structure and social satire.

At their core, both productions offer youthful yet timeless observations on social class, romance, and the complex journey toward self-knowledge during formative years. Clueless brought Austen’s subtle wit and social commentary into the contemporary vernacular for a new generation in a bright, breezy adaptation. The film proved her themes remain as relevant as ever, whether amongst 19th century English countryside or 1990s Beverly Hills high society.

Trading Places (1983)

While Trading Places was not directly based on The Prince and the Pauper story, it certainly drew influence and parallels from Mark Twain’s classic tale of social role reversal.

The 1983 comedy directed by John Landis stars Dan Aykroyd and Eddie Murphy in a comedic twist on class roles. Murphy plays a streetwise hustler who is brought low after losing his job and home, while Aykroyd portrays a wealthy commodities broker. The two men become pawns in a bet between elite businessmen, where they swap social classes on the whim of others.

Much silly humor arises from seeing Aykroyd struggle with poverty as Murphy acclimates to privilege. But underneath the raucous farce lay thoughtful echoes of Twain’s insight – that outward trappings of class often fail to define a person’s true character or potential. Both works suggest those on top may lack skills to cope below, and hidden capacities can emerge when circumstances change one’s place in society.

While Trading Places puts a ’80s twist focusing more on laughs than morals, the seed of its idea stems from Twain’s age-old story demonstrating how superficial facets like birth, money and status ultimately mean little. Perhaps the tradesome antics of Aykroyd and Murphy introduced a new generation to evaluate social constructs, as Twain had for his time, in a entertaining package reflecting the spirit if not direct lineage of The Prince and the Pauper.

The Lion King (1994)

While The Lion King presents itself as a story about a lion cub who struggles to accept his destiny as king, the 1994 Disney animated classic actually takes much of its dramatic structure and plot points from Shakespeare’s famous tragedy Hamlet.

In Hamlet, the prince of Denmark learns his uncle Claudius murdered Hamlet’s father to seize the throne and marry Hamlet’s mother. Similarly, in The Lion King young Simba learns his uncle Scar killed Simba’s father Mufasa to be king and tries to have Simba killed as well.

Both works involve a betrayal of the rightful heir to the throne by a trusted family member. Grief and the drive for vengeance propel the main characters as they wrestle with doubt, madness and a desire for justice. Like Hamlet, Simba flees only to later return prepared to face his foe, with the climactic confrontation occurring in front of the usurped throne.

While transplanting it to an animal kingdom with songs and family friendly adventure, The Lion King follows Shakespeare’s framework remarkably closely. From parallels between Scar/Claudius and Mufasa/King Hamlet to motifs like graveyards, regicide and madness, the animated epic brought these classic themes to new audiences in visually stunning form. It showed how Shakespeare’s understanding of betrayal, destiny and the costs of revenge remain potent regardless of the setting or characters. For many kids, Simba’s story may have first sparked an interest in the Bard’s enduring works.

Godfather Part III

While Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather Part III (1990) took a more biblical approach than its predecessors, it did draw parallels from Shakespeare’s tragic play King Lear in its depiction of Michael Corleone.

In King Lear, the aging king descends into madness after foolishly dividing his kingdom between two deceitful daughters, while favoring the honest third. Michael Corleone similarly makes rash decisions late in life that end up strengthening his enemies while losing the loyalty of those closest to him.

Both protagonists cling desperately to power even as it slips from their grasp. By the climactic third acts, both Michael and Lear are left with nothing, having brought ruin upon their families and empires due to tragic flaws of arrogance, poor judgment of character and refusal to relinquish control.

While the settings and specifics differ, The Godfather Part III saw Michael’s criminal empire meet its demise in part due to some of the same mistakes of ego, paranoia and failure to pass the torch that led to King Lear’s tragic downfall. This added new dimensions of pathos and Shakespearean tragedy to Michael Corleone’s Shakespearean conclusion as the once mighty don is forced to face his mortality alone and in disgrace at the end.

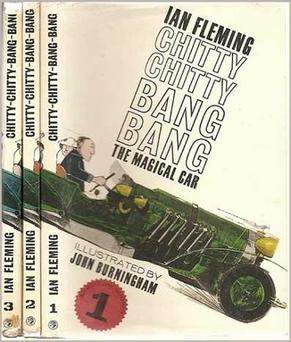

Chitty Chitty Bang Bang

While best known as the author of the iconic James Bond spy novels, Ian Fleming also wrote an exciting children’s adventure story titled Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang.

Published in 1964, the novel Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang followed the exploits of eccentric inventor Caractacus Potts and his family. Potts rebuilds a magical and musical antique car that takes them on magical journeys. The story incorporated elements of fantasy, adventure, humor and imaginative vehicles that appealed to both children and adults alike.

The 1968 film adaptation directed by Ken Hughes brought Fleming’s whimsical tale to life. Starring Dick Van Dyke and Sally Ann Howes, with iconic production design by John Blanche, the live-action musical captured the spirit and magic of Fleming’s car that could fly.

Both the book and movie have enchanted generations with the charm and imagination of Potts’ fanciful flying contraption. It showed Fleming’s superb storytelling gifts extended beyond the espionage genre. Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang proved some of literature and cinema’s most beloved works have verve to cross genres and appeal to all ages through vivid adventure, humor and timeless themes of family bonding.

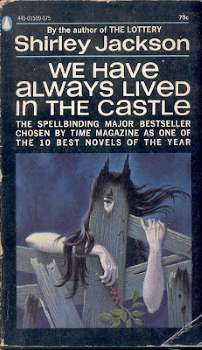

We Have Always Lived In The Castle (2018)

We Have Always Lived in the Castle, a film adaptation released in 2018, brought Shirley Jackson’s haunting novel of the same name to the silver screen with a unique blend of visual storytelling and atmospheric cinematography.

Published in 1962, We Have Always Lived in the Castle is a psychological Gothic mystery novel told from the perspective of 18-year-old Mary Katherine Blackwood. Mary Katherine lives with her crippled and reclusive older sister Constance in their decaying family mansion in a small Vermont town from which they are largely isolated due to a tragic event six years prior.

With a meticulous attention to detail, the film successfully translates the unsettling ambiance of Jackson’s novel onto the screen, offering a visually compelling and emotionally resonant adaptation for both fans of the original work and newcomers alike.